I've seen a few partial solar eclipses, but my first total eclipse was in Idaho in August of 2017. I happened to be on fieldwork at the Craters of the Moon National Monument for the week preceding the Monday morning eclipse, and this put me very close to the path of totality. It was a relatively simple thing to take an extra day to witness the event.

This year's eclipse took a little more effort. But my schedule at work was especially heavy in the months preceding the eclipse, and it made sense to plan for a vacation when things were expected to calm down a little in April. The path of the eclipse passed through Mexico and Texas, then northeastward towards the lower Great Lakes, and through New Brunswick and Newfoundland. Any of those could be reached pretty easily with an airline flight and a rental car, but Texas was the obvious choice if I wanted to fly there myself.

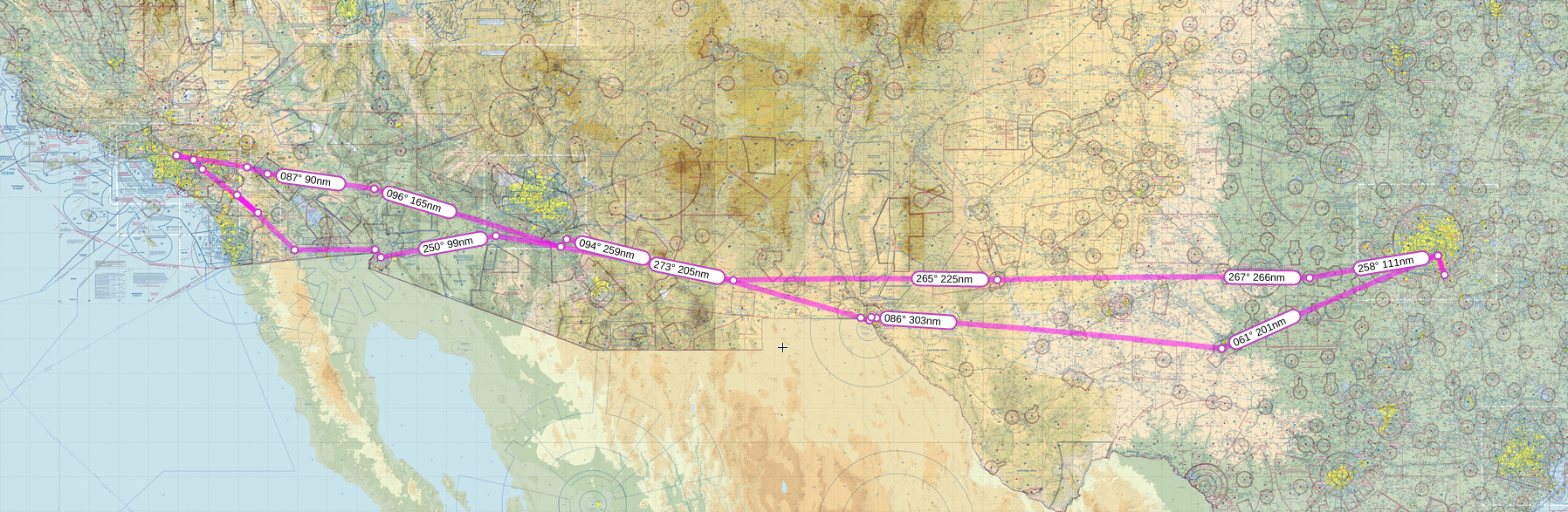

Fly out from El Monte on April 4th. With a roughly three-hour flight in the morning and another in the afternoon, and time in the evening to review the weather and plan routes and stops, it should optimistically take two days to reach Dallas, near the centre of the path totality, and home to my friend Aaron, who was eager to see the eclipse and had offered to let me stay with him while I was in town. With the eclipse happening in the afternoon of April 8th, that gave me two, even two and a half days margin on a two-day flight plan, which seemed like enough. To return, I could fly out on the morning of the 9th, and, working against the prevailaing westerly winds, take perhaps two and a half days to get back to El Monte. If conditions warranted, I could speed things up with an early departure late on April 8th, or with a three-flight day to cover more ground.

Initially I was considering additional stops in Kansas, Oklahoma, or Colorado on the way back, but during the planning phase I ended up booking a (commercial) flight to Europe for April 13th. This meant I was down to about 100% schedule margin to get home in time, so the return strategy became a focus on rapid progress towards El Monte. I booked an afternoon flight to Amsterdam, in case I needed to use that Saturday morning to cover the last bit of distance before rushing off to LAX, and selected a changeable fare, just in case even that wasn't enough to make my airline flight in time.

The plane for this trip: the Caltech flying club's N98326, a Cessna 172 which had been my companion on some previous trips, and was available for the second week of April (booked well ahead).

Tuesday night, April 2nd, the forecast for the Los Angeles area showed rain on Thursday the 4th, and on Friday the 5th, with some models extending even into early Saturday. This most likely would keep me on the ground until it was over, using up all of my schedule margin right at the start of the trip, and throwing the entire idea of reaching Dallas for the eclipse into doubt. Wednesday morning, the 3rd, I woke up ahead of my shift of SuperCam instrument operations and saw that the aviation forecast really was no good at all from sometime in the early morning of the 4th.

A notion which had occured to me on Tuesday night became more real: what if I just packed up and left on Wednesday, before the weather rolled in? I had to work the SuperCam shift, but I could get going after that. And I didn't have to do a long flight, just get far enough east to escape the system which would roll into the Los Angeles basin. A quick look at the forecast and the route map over breakfast suggested this would work if I got at least as far as Palm Springs. N98326 was available in the evening, so I extended my booking, and went to get ready for rover ops.

Of course, this would be the day when the downlink processing of data from the previous Perseverance rover plan would be delayed, slowing things down and delaying the end of my ops shift. Nonetheless, the team ultimately got it done and we prepared new uplink sequences for the rover, including, for SuperCam, targets selected both by the human team (me and the scientists online) and the onboard computer (using the AEGIS autonomous targeting software). It was a full day, and I was about to have a full evening.

I packed up very quickly (it was going to be a short, simple trip after all) then reviewed the weather and planned out some flight options. The bus-train-bus to the airport got me there a little before sunset, and by the time I took off, it was dark. It was a beautiful evening, with smooth flying but no moon to light the mountains. Careful navigation is called for in darkness like that. Flying high to avoid terrain and busy airspace, I made it through the Banning pass between entirely invisible mountains, only to reach some of the bumpiest air I've encountered, during the descent into Palm Springs. I also lost radio contact with the approach controller, perhaps due to the steep surrounding terrain, which made for a hasty contact with the tower and arrival into Palm Springs. But I made it, and after parking the plane, booked a nearish hotel, pulled my folding bike out of the back seat, and pedaled over to check in, plan the next day's flights, and sleep.

Thursday morning I awoke to a beautiful view from my hotel room window: clear blue skies, palm trees, those previously unseen mountains, and, lurking in the pass I'd flown through, a shelf of thick cloud. I'd made it just far enough to escape that weather system - the hasty departure had paid off.

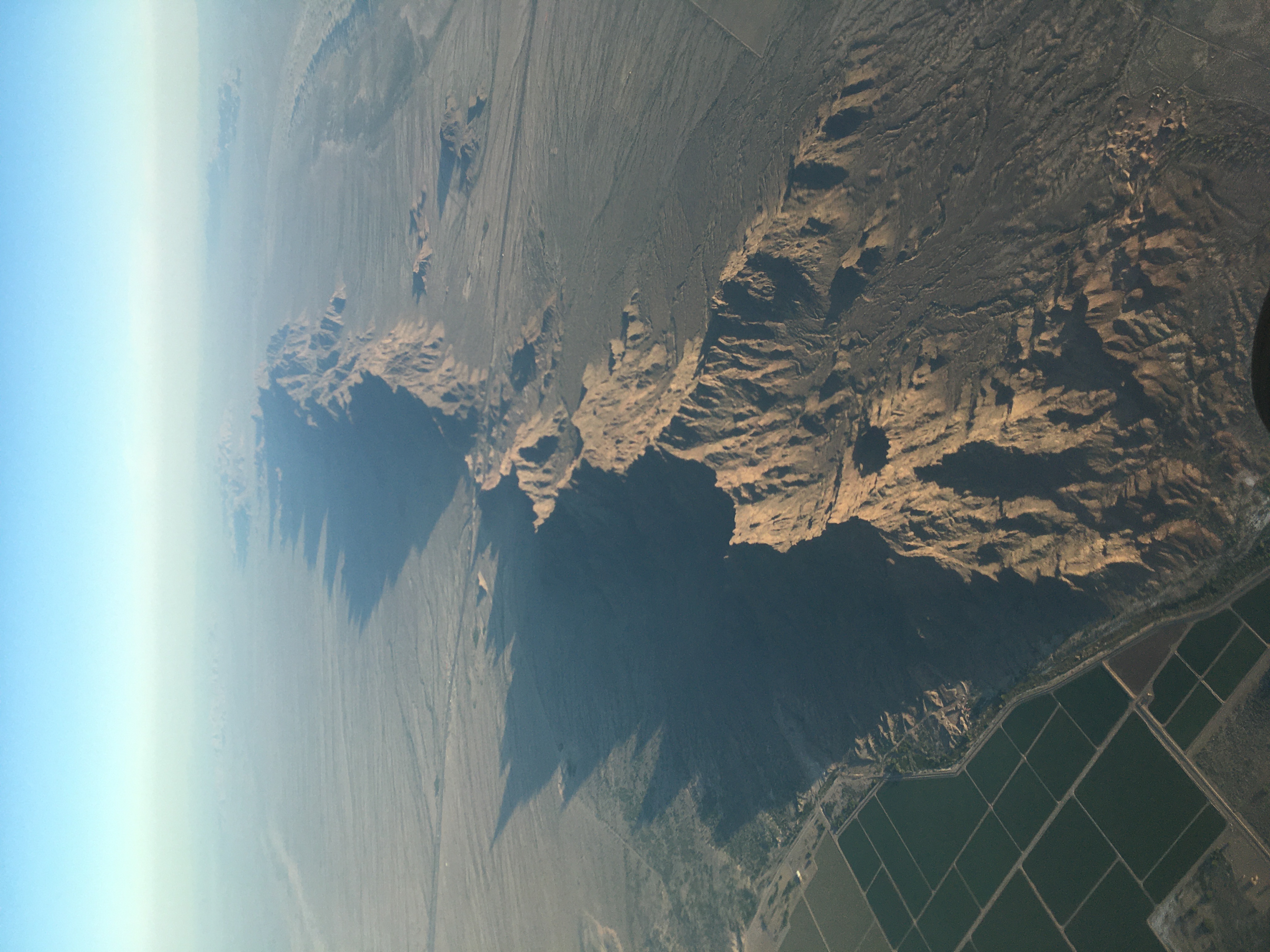

The rest of Thursday was pretty easy. I flew to Eloy, Arizona, a place I'd once spent the night on the way to Santa Fe, and had lunch while updating the weather, video calling Tom, and watching the Twin Otter full of skydivers come and go. From there, I headed only a few miles north to get around some high terrain, then made a beeline for El Paso, Texas. The arrival there, just after sunset, was gorgeous, with the golden light, the glittering city, and the mountains as dusk turned to darkness.

That night's forecast showed challenging conditions the next day, with a band of strong winds in central Texas. It was hard to find an airport with fuel, favourable winds, and a time-efficient lunch option which was also at about the right distance to let me reach Dallas in two hops, with conservative fuel planning. I settled on Big Spring as my mid-day fuelling point, and went to bed.

Friday morning showed a change in that forecast, and I had to make a new plan over the hotel breakfast. A lengthy call with the weather briefing service convinced me to change it again, and I set off for San Angelo.

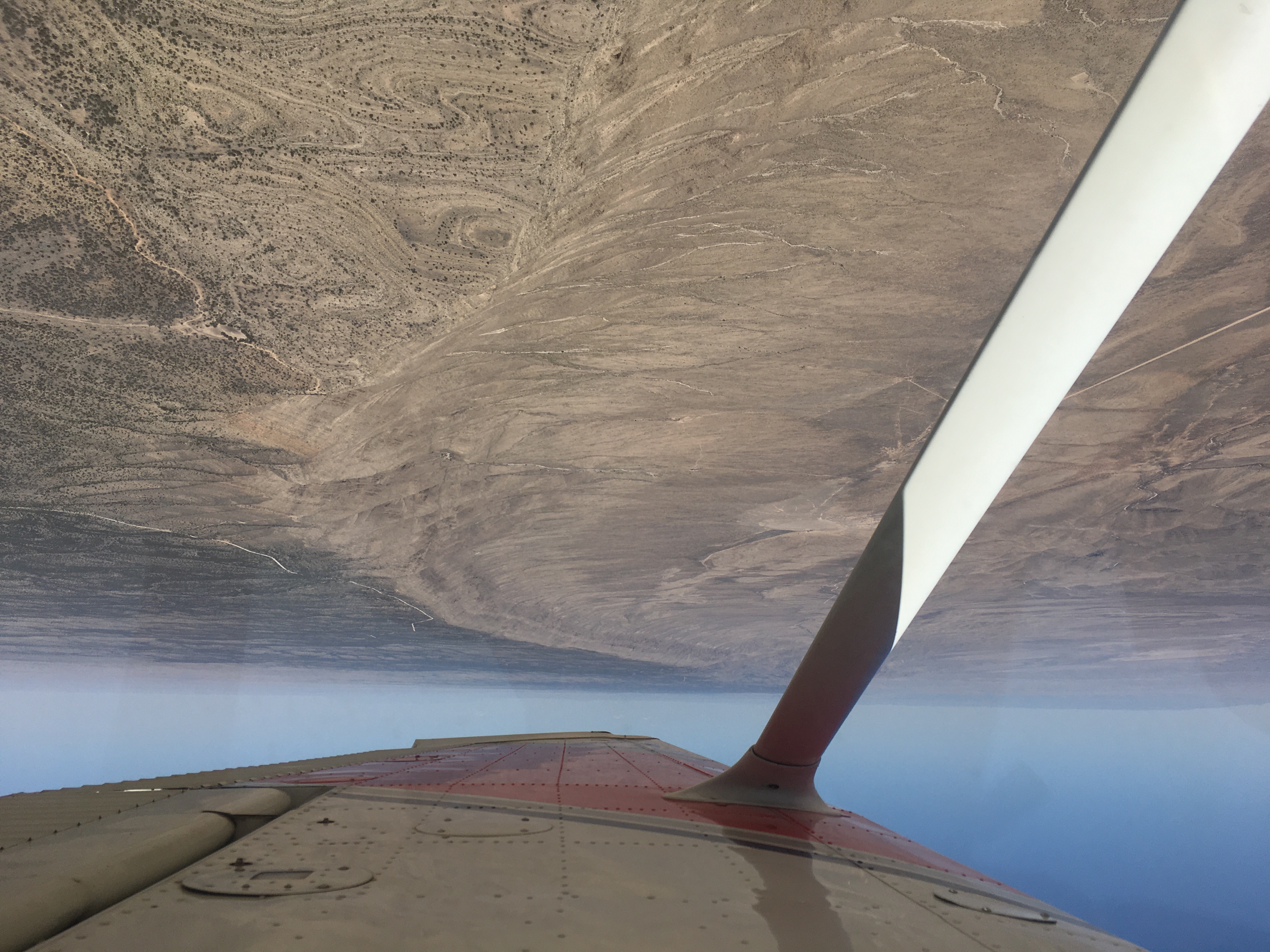

Now, aerial sightseeing is a big part of why I enjoy these cross-country flying trips, and California, Arizona, and New Mexico rarely disappoint. On a trip from the Los Angeles area to El Paso, you're over desert nearly the whole time, but it's very scenic desert. Lava flows, dune fields, mountains of igneous rock here and sedimentary rock there, interspersed with some sparse settlement and in places agriculture. You sometimes have to plan routes to clear the terrain, and you end up studying the landscape closely to monitor for emergency landing options, so you end up spotting a lot of interesting things.

Texas is different. Not far east of El Paso, it flattens out, and you're in a new kind of desert. One which extends as far as the eye can see, even from a few thousand feet up, and continues for a couple of hundred nautical miles of flying in a straight line. It's a desert of sparse brush, and many, many oil and gas wells. Each has a dirt road running to it, and here and there you spot larger facilities, some of which are flaring off natural gas in flames which are very visible from the air. There's a lot of this terrain, and it's enough to explain how West Texas Intermediate is one of the main standards for crude oil prices.

The winds at San Angelo were stronger than forecast, but straight down the runway. The lunch routine was was much like the day before, and I set off for the final two-hour leg to Dallas. Just after takeoff, I first heard an aircraft on approach, and then heard the tower tell a second approaching aircraft that the into-wind runway was unavailable due to a diasabled aircraft occupying it. I likely would have been stuck in San Angelo had I taken off any later; I wouldn't have wanted to takeoff with crosswinds as strong and gusty as they were.

After San Angelo, the terrain changes. Now it's green fields, patches of trees, and a lot of artificial reservoirs. Eventually you reach the suburbs of Dallas, over which you fly for quite a while before you actually spot the city itself.

Aaron and his husband Justin met me at the airport. We spent the weekend touring the city a bit, dining in and dining out, visiting the local aviation museum, and also taking a quick local sightseeing flight.

We were also periodicially reviewing the weather forecast, and gradually making plans. By Sunday afternoon it very much looked like Dallas would be cloudy for the eclipse, and that wouldn't do. With a combination of aviation forecasts and public weather modeling tools, we decided that northwest Arkansas was the area of the eclipse totality path which was within reach and had the best chance of clear skies for the early-afternoon event. And we decided that given the weather expected soon after the eclipse, Aaron's car would be a better choice than the airplane to get there.

We spent the night in Searcy, Arkansas, at a hotel whose parking lot displayed a very noticeable diversity of licence plates from as far as Mexico. In the morning, a review of the latest forecasts led us to try for the area around Russellville, with plans to divert southwest or northeast as conditions warranted.

We ended up in a park outside of Russellville, which was busy but not overwhelmed. The partial eclipse had been underway for some time, but we still had nearly an hour to totality. The sky was blue, with a few clouds about, and the view from the ground and the satellite images suggested that, despite a lot of cloud in the region, this area would likely be clear for a while. Other people in the park had brought picnic lunches, a few had small telescopes. Most were in small groups, waiting. Things were calm - so much so that you could easily hear the crickets and frogs as they started up when the sky got dim enough.

When the moment came, the viewing conditions were perfect. For four minutes and eleven seconds, the incomparable spectacle hung in the sky, above the trees, unobsctructed by cloud. The corona was clearly visible, as well as a few small solar prominences, and Jupiter and Venus were clearly in view as well. I don't have any photos worth sharing (try these); I didn't have a camera suited to the task, and instead I laid down on the ground and gazed up for the last couple of minutes.

A thousand wondrous things happen around us every day. Clouds form, drift, dissipate, perhaps drop rain. Birds sing in the trees, bees tour the local flowers and make honey. Distant stars shine from their own weight squeezing atoms til they fuse, and remain visible across vast and barely comprehensible distances. But a total eclipse, though inevitable as a consequence of the motions of the moon and the earth, is a wondrous and extraordinary thing. The corona extending out into the darkened sky around the black moon, hanging seemingly still above ordinary, familiar trees and other objects, is a reminder that the universe is set up to regularly produce stunning, if often unnoticed, wonders.

After all, at any other time, in any other place, this tremendous spectacle would be easy to ignore - most parts of the earth did not see an eclipse at that moment, none did a few hours earlier, and the partial eclipse can be hard to notice. But we live in a time when thousands of years of human progress have allowed us to predict the motions of the planets with great precision, and so we can know where and when to see events which, though routine, are infrequent on the scale of human lifespans. And thus to be reminded of how marvelous it is to live on the surface of this world, only a thin layer of air between us and the other revolving orbs.

During the afternoon of the eclipse, and the following days, I had several interactions with people who, despite having to work or tend to other responsibilities, had taken the time to see the eclipse. Most weren't specialists or even hobbyists in planetary science or astronomy - these were diverse people with diverse lifestyles and schedules, but they'd made time for it. It was nice to see that taking a moment to witness the wonders of nature was so widely seen as worthwhile, and that the people I spoke to weren't prevented from seeing it by a petty supervisor or bureaucratic constraint. There's room for joy and wonder, it seems.

We hit the road a few minutes after totality ended, having several hours of driving to do to get back to Dallas, and with Justin and Aaron both having to work the next day. I spent the car ride back assessing the weather for a flight westward to return to California.

It became very clear that the weather was so-so in Dallas (we probably would have seen the eclipse partially obstructed between broken clouds) and getting worse, and that it would be no good for flying for probably the next two days. If true, I'd lose all of my schedule margin on the two-and-a-half-day trip home, and I was thus very movitaved to find a way out that evening, even as I was watching the weather close in on Dallas while riding towards the city.

A band of thunderstorms extended east-west to the south of the city, moving east-northeastward. Low cloud and showers were to the northeast, and to the northwest, some distance away, was a large area of storms. At first it seemed like a sufficiently early arrival in Dallas would allow a departure westward to get past the storms before they closed in, but it became clear the area to the west would be affected as well. There was also a significant gap to the north, though, and I planned a route to the north and arcing to the northwest, flying over Oklahoma to the northeast corner of Texas and avoiding the forecast area of the storms. The next day I'd be able to fly southward towards southeastern New Mexico, over areas the storm would have passed.

There were three problems with this plan:

It's fun to be inventive and come up with clever solutions to challenges, but you should do everything possible and no more, so my next call was to the FBO to get the aircraft put into a hangar for the next couple of days. I spent the next two days in Dallas, leaning on Aaron and Justin's generosity as hosts, reviewing weather forecasts, and making plans for how to get home depending on when I might be able to leave.

On Wednesday April 10th the weather was still bad, but forecast to clear up overnight. A review of forecasts for the next day suggested favourable winds over the southwest US which might shorten a two-and-an-half-day trip to two days, but that by late Friday or early Saturday, a new weather system would move into southern California, and potentially stay for days. If I wanted to make that flight to Amsterdam, I'd need to make very good use of Thursday, and any progress I could make Wednesday night would be a big help.

I picked a couple of destinations with suitable services, about a one-hour and two-hour flight westward, planned out the flights, and set deadlines for that evening. If the weather improved by 19:00 or 20:00 local, I could launch and do the two- or one-hour flight, and get some distance behind me that evening while still leaving time for flight planning, forecast review, and adequate sleep before a long Thursday of flying.

As it turned out, the weather did improve, and the low ceiling cleared out just around 19:00 local time. I took off into clear skies with smooth air, flying low over the suburbs below the DFW airspace, then climbing up for the cruise portion. It was a straight shot to Cisco, Texas, where I landed in the dark, fuelled the plane, unfolded the bike, and went to spend the night at the Lone Star Motel.

Thursday was the big day. The wind forecast seemed to be holding, and it looked like I could make good time. There aren't that many places to stop, but starting in Cisco meant, with those winds, I was well staged to do a three-hour flight to Carlsbad, New Mexico, then about two and a half hours to Lordsburg, and from there either two hours to Gila Bend, Arizona, or three to Yuma. Yuma would put me an hour and a half from home, but even Lordsburg would set me up for getting to El Monte in two hops, the next day.

I got an early start, and climbing through clear but bumpy air I quickly got into the forecast tailwinds. It was hazy, and bumpy, once I crossed into New Mexico, and I only spent enough time in Carlsbad to have a quick lunch of delivery pizza, a short call with Tom, and a check-in with the weather briefer. Then it was off to Lordsburg, where winds over the mountains of southern New Mexico made for an at times rough ride.

Lordsburg is a long way from anywhere else, but it has a nice little airport, which is apparently the oldest in New Mexico. It has just what you want to find at a small airport: a restroom (with even a shower) and a source of drinking water, fuel, and a comfortable indoor space for flight planning. In fact, it's clear a lot of care went into this place. While the building is old, it's been well-maintained, and it's got maps, books and videos about flying, photos of the airport from decades ago, airplane models on display, and a bowl of mints. Someone takes care of that place, with an eye no doubt to the comfort and needs of both local and itinerant pilots.

The sky was clear and blue, and the scenery was gorgeous, all the way across New Mexico and into Arizona. Things were still going well as I approached Gila Bend, and I carried on to Yuma, where I landed just after sunset.

I was now within striking distance of home, and the weather forecast looked good for the next day - a bit of morning fog in the Los Angeles basin, perhaps, but then clear in the afternoon before the weather rolled in overnight. A single flight would easily do it, and would in fact pass right by the gliding strip at Warner Springs, where I could stop to fly gliders while waiting for the fog in Los Angeles to clear. I went to sleep with my plans made.

I woke up to find my plans unmade. The morning fog was now forecast to persist, and cloud was moving in from the ocean. It was expected to clear for a few hours before the weekend weather arrived early. After a lot of replanning and weather review, it seemed to make sense to strike out for El Monte, aiming to arrive at the start of the clearing window, and diverting to French Valley, Hemet, Perris, or places closer to El Monte, if needed. Gliding would have to wait - the priority was getting home.

I flew westward, just north of the Mexican border, then turned northwest over the mountains. As expected, the valley around Warner Springs was clear, and I passed overhead, all the while checking weather broadcasts at various places along the route and near home. French Valley had by this point clouded over with a very low ceiling, and Hemet had gone from clear to scattered. As I passed east of the Palomar observatory, and approached the edge of the cloud deck that was filling the valley, the hourly weather observation broadcasts updated. El Monte and nearby Bracket were still clouded over. It was either carry on the long way, over the edge of the cloud, northeast to Palm Springs, which was still clear, or turn back to Warner Springs. I chose the latter.

I did do a little glider flight while I waited, but with my attention very much on the evolving weather situation, I spent most of my time on the ground reviewing forecasts and making plans. And waiting.

By late afternoon, the weather still wasn't looking promising, and in fact the clouds were starting to spill over the mountains into the valley around Warner Springs. It's about a one-hour flight to El Monte, and I had nearly three hours of fuel on board (counting conservatively). The clouds were expected to thin out for about four hours, starting about three hours before sunset - a somewhat hopeful forecast, but not the kind you can rely on. Warner Springs not being a convenient place to spend the night (the only hotel is closed), this set me up for the following plan:

In either diversion scenario, I would land at the diversion point around sunset, with nearly an hour of fuel margin.

The clouds threatened Warner Springs, but didn't close in. I launched at the planned time, and headed for El Monte. By the time I approached French Valley, the clouds there were breaking up, and there was noticeable clearing ahead. I proceeded over the cloud layer, with confident navigation references both laterally and below. By Lake Elsinore, a large hole in the cloud deck had opened up, and the weather broadcasts showed that both El Monte and Brackett had signficantly higher ceilings (high enough for VFR flying), though still overcast. Corona, just beyond the cloud gap around Lake Elsinore, had ceilings over 3000 feet, also a big improvement.

I elected to descend over Elsinore, and kept as high as I could below the cloud deck. It wasn't clear there would be another gap closer to El Monte, and this approach would get me below the LAX class-B airspace. At Corona, the ceilings were still plenty high, and in fact several aircraft were about, both in the circuit and transiting from elsewhere. This was good news - if I proceeded further and found lower than expected ceilings, I could simply turn around and land at Corona. (El Monte being so close, it was unlikley Corona would suddenly close in from 3000+ foot ceilings to unflyable, and I could monitor the minute-to-minute ceilings at Corona as I continued flying.)

In the end, I was able to keep well clear of clouds, well above obstacles, and in solid 10+ mile visibility the whole way to El Monte, though I did have to descend a bit below 3000 feet. I made an easy landing in good conditions. Those clouds never did clear as forecast, though they did lift over the next couple of hours to some 4000 feet overcast. Overnight, the rainy weather set in.

I put N98326 to bed, packed up my things, and took the bus, train, and bus to Altadena.

The final distance was over 2300 nautical miles, with 25.3 hours in the air (not counting the glider flight).

The trip did its job - I got to see the eclipse and visit my friends, see some new places, and enjoy some gorgeous aerial sightseeing. But it also challenged me to use all my skills for flight planning and meteorology, both on the ground and in flight. And to make decisions, without sacrificing safety, as conditions change and goals seem to be slipping away. Old lessons from ground school and flight training came back to me many times, about having respect for the limitations of weather, of the aircraft, and of human factors. I recognized the stress of the schedule pressure, and chose not to do an advanced gliding lesson with the instructor who was available, knowing that I'd do a worse job of learning challenging things if I was distracted by my weather problem. And I had multiply-redundant plans all along - most of which I never had to invoke, either because I chose not to launch, or because conditions weren't as bad as the scenarios I'd prepared for. That's a good outcome.

We'll see where the next trip takes me, but it'll probably be something with more schedule flexibility than a solar eclipse - there won't be another one in this part of the world for decades.

Aboard KLM 603

2024-04-21

Special thanks to Aaron Brown and Justin Martin, for being such gracious hosts as I waited out the weather in Dallas, and for a great weekend of exploring Dallas and chasing the eclipse across Texas and Arkansas.